by D. J. Green | Mar 14, 2018 | Ground Work

I need it. To feel small, even insignificant, in the face of nature’s works nourishes me. I seek that nourishment daily.

From my home at the base of the Sandia Mountains to the beautiful old Mabel Dodge Luhan House at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in Taos, I drove for miles alongside the Rio Grande as the road climbed from Española into the gorge of the river that flows from a source high in Colorado’s Southern Rockies to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico. It rippled over basalt boulders that had tumbled into its bed from the steep slopes above. Winter bare cottonwoods revealed their convoluted forms, another of nature’s graceful sculptures. Light glinted off the faces of boulders burnished with desert varnish. I imagined the music of the river, a constant murmur, overshadowed that day by the whoosh of the wind, whose gusts the soaring crows danced upon, riding waves of air. I could drive this stretch of road every day, and still it would inspire my awe.

From my home at the base of the Sandia Mountains to the beautiful old Mabel Dodge Luhan House at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in Taos, I drove for miles alongside the Rio Grande as the road climbed from Española into the gorge of the river that flows from a source high in Colorado’s Southern Rockies to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico. It rippled over basalt boulders that had tumbled into its bed from the steep slopes above. Winter bare cottonwoods revealed their convoluted forms, another of nature’s graceful sculptures. Light glinted off the faces of boulders burnished with desert varnish. I imagined the music of the river, a constant murmur, overshadowed that day by the whoosh of the wind, whose gusts the soaring crows danced upon, riding waves of air. I could drive this stretch of road every day, and still it would inspire my awe.

That awe, the wonder of nature – from the minute gleam of an obsidian ‘Apache tear’ glimpsed on a trail to the mighty basalt cliffs that tower over the narrowest reaches of the Rio Grande Gorge – provides perspective that helps me handle the shock and awe (of a much different sort) that assails on a daily basis, reading the news of humans seemingly endless supply of inhumanity.

Nearly every day (yes, sometimes I forget), I walk in gratitude to live in places were nature is so reachable. I can touch the paper thin wisp of a seed pod. I can hear it rattle in the breeze. I can watch a lizard no bigger than my pinky finger scurry into the protective spines of a prickly pear’s paddles. I hear the coyotes’ howls echoing through arroyos, their pups’ yips and yaps new voices in nature’s song. But even in the city, there is birdsong, the rustle of bare trees’ branches in the wind, and the occasional passing of a coyote. Wherever I am, I can find it – awe – if I remember to look, to listen.

Nearly every day (yes, sometimes I forget), I walk in gratitude to live in places were nature is so reachable. I can touch the paper thin wisp of a seed pod. I can hear it rattle in the breeze. I can watch a lizard no bigger than my pinky finger scurry into the protective spines of a prickly pear’s paddles. I hear the coyotes’ howls echoing through arroyos, their pups’ yips and yaps new voices in nature’s song. But even in the city, there is birdsong, the rustle of bare trees’ branches in the wind, and the occasional passing of a coyote. Wherever I am, I can find it – awe – if I remember to look, to listen.

The next morning, I woke to the hush that blankets the landscape with even a dusting of snow. Always a blessing in the desert, this winter any moisture is a particular gift given the parched season we’ve had. I scooped up a handful, and as I lifted it to contemplate the intricacies of the delicate flakes, the sun peeked through a cloud break and shone over my shoulder. Nature’s wonder sparkled there, right in the palm of my hand.

The next morning, I woke to the hush that blankets the landscape with even a dusting of snow. Always a blessing in the desert, this winter any moisture is a particular gift given the parched season we’ve had. I scooped up a handful, and as I lifted it to contemplate the intricacies of the delicate flakes, the sun peeked through a cloud break and shone over my shoulder. Nature’s wonder sparkled there, right in the palm of my hand.

by D. J. Green | Mar 1, 2018 | Ground Work

Hat pulled low, hands cozy in ski mitts, I wiggled my toes to keep them warm in wooly socks. I walked from the lodge to Old Faithful Geyser in the dim light of the winter evening. The snow compressed beneath my boots, squeaking with each step. The sounds of snow – one of the many things I love about winter.

I left the others seated by a crackling fire after one of the finest days of cross-country skiing I’d ever had – the weather, cold enough not to get overheated skiing, but warm enough to stop and enjoy the landscape and wildlife; the snow perfect; and the company, the best of friends. After skiing together to Lone Star Geyser in the morning, we’d all chosen different routes back. That evening, my friend, Nancy, and I still glowed from our afternoon’s accomplishment. We’d taken a beautiful, but tough trail back. We’d fallen plenty and stopped to catch our breath more, but we’d done it! We definitely earned the thousand-calorie Belgian hot chocolate we indulged in upon returning.

I left the others seated by a crackling fire after one of the finest days of cross-country skiing I’d ever had – the weather, cold enough not to get overheated skiing, but warm enough to stop and enjoy the landscape and wildlife; the snow perfect; and the company, the best of friends. After skiing together to Lone Star Geyser in the morning, we’d all chosen different routes back. That evening, my friend, Nancy, and I still glowed from our afternoon’s accomplishment. We’d taken a beautiful, but tough trail back. We’d fallen plenty and stopped to catch our breath more, but we’d done it! We definitely earned the thousand-calorie Belgian hot chocolate we indulged in upon returning.

I made my way to the boardwalk and benches surrounding Old Faithful that overflows with people from around the globe on summer days. In the crisp cold a crescent moon shone through wispy clouds whisking on the wind, the stars blinked, and I was the only one there. Well, the only human. If others were nearby, bison or coyote, perhaps, they didn’t make their presence known to me. I hoped I wasn’t disturbing their peace, they get gawked at enough (by me too, whenever I have the opportunity).

Old Faithful is faithful, but not exact. Eruptions occur roughly 60 to 100 minutes apart, plus or minus 10 or more minutes. Never silent, the geyser spurt and sputtered, and each time I wondered if the eruption was starting. Natural hot springs that don’t always flow, geysers erupt steam and water, sometimes high into the air, at varying or somewhat regular intervals depending on the configuration of their underground ‘plumbing.’ That isn’t piping, of course, but the natural conduits in the bedrock through which water and steam rise from the subsurface.

I strolled along the boardwalk, built to protect the fragile crust of travertine from the hordes who come to see and hear and feel this wonder of nature. I waited patiently, at first. I turned my back to the wind for a while, then jogged in place, kept moving to stay warm. Three, four, five times, steam and water shot a few feet in the air. I could hear the droplets raining down on the surrounding stone. Then it would settle. I began to think I’d missed the eruption by a few short minutes.

I strolled along the boardwalk, built to protect the fragile crust of travertine from the hordes who come to see and hear and feel this wonder of nature. I waited patiently, at first. I turned my back to the wind for a while, then jogged in place, kept moving to stay warm. Three, four, five times, steam and water shot a few feet in the air. I could hear the droplets raining down on the surrounding stone. Then it would settle. I began to think I’d missed the eruption by a few short minutes.

Even if I did, I couldn’t complain. On our first day here, it seemed that every geyser we skied up to, erupted just as we pulled our cameras from our pockets. Bison had posed, the sun glowing on their thick coats. A coyote had lingered along the fence overlooking Punch Bowl Spring, despite five of us skiing to within fifty feet or so. Pawing at the frozen ground, he feasted on some morsel while we watched, his golden eyes peering at us now and then to make sure we kept our distance. He’d run away when the spring began to thump. We could feel the vibration from the ground up through our skis into our legs, the hum of Earth’s geothermal ‘engine’ so near the surface in Yellowstone.

.

When the hiss of steam grew louder, then rose to a rumble, there was no mistaking it, I had not missed the eruption. Hot water gushed forth, a cloud of steam billowed high. I’m sure there are many people who have been a lone witness to this, but I felt (and still feel) immense gratitude for those moments, standing beside Old Faithful, alone.

Our oldest National Park, established on March 1, 1872, Yellowstone is a magical place in every season. But the beauty of this natural gem truly shines in winter – I wish I could capture the way the sun sparkles on fresh snow, the shush of Spring Creek, the hot springs’ sulfurous scent, the way snow cakes in the fur of a bison’s massive head as it grazes, or the glub of boiling mud in the Fountain Paint Pots. But I can’t. You’ll just have to go.

Happy Birthday, Yellowstone National Park!

Happy Birthday, Yellowstone National Park!

Many thanks to Eric Hubbard for his wildlife pictures from the trip.

by D. J. Green | Feb 5, 2018 | Finding the Words

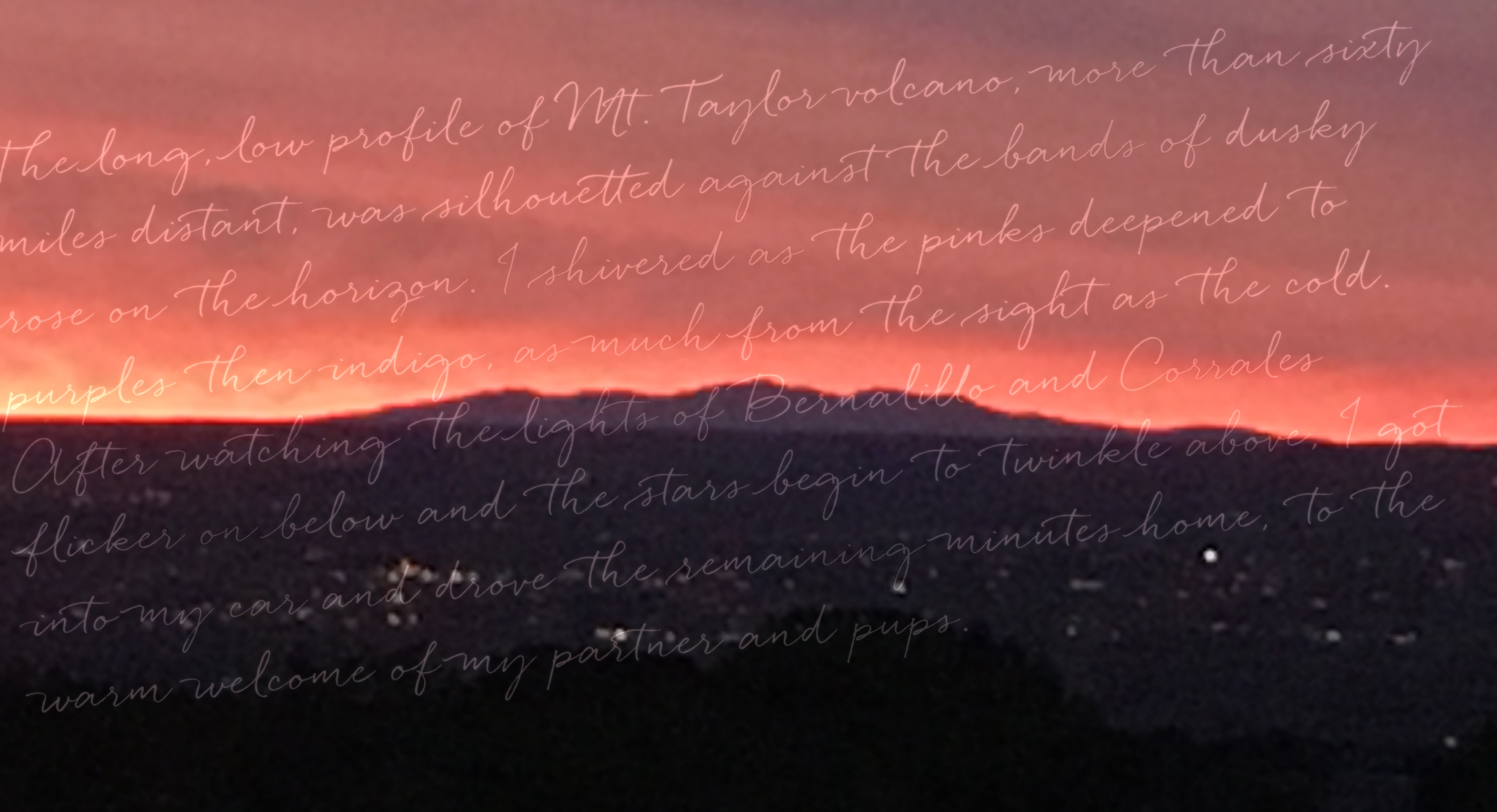

I stole glances at the sunset over my left shoulder as I drove north, from work toward home. Clouds swept the western horizon, spreading the orange glow of the sinking sun. Broad brushstrokes of color painted the sky.

Turning onto the rural lane I live on, I pulled over, the tableau now laid out before me. I had to stop. I climbed out of the car, zipping my jacket against the early evening chill, and gazed to the west.

“Wow,” I whispered.

I reached back into the car for my iPhone. Snapping photos, I missed precious moments of the shifting sunset’s fire. Then I remembered to simply witness – to let the beauty of those moments paint a picture in my memory.

The long, low profile of Mt. Taylor volcano, more than sixty miles distant, was silhouetted against the bands of dusky rose on the horizon. I shivered as the pinks deepened to purples then indigo, as much from the sight as the cold. After watching the lights of Bernalillo and Corrales flicker on below and the stars begin to twinkle above, I got into my car and drove the remaining minutes home, to the warm welcome of my partner and pups.

That night, and in the days that followed, the idea of painting a picture with words, rather than submitting to the impulse to grab for my phone, percolated.

It’s what I hope I’ve accomplished in my novel – that I’ve created a world with words – a landscape vibrant with sunrises and sunsets, along with cinder-block houses, a bustling office, rattling cars, and a sky-blue Cessna. Have my brushstrokes made that world vivid enough for you to want to explore it? Have I populated that world with characters you’ll see and hear and feel? Characters you’ll want to know, though they only “live” on the pages you’re turning?

That’s one of the challenges of writing – to create with mere words, black and white on the page, the picture of your brilliant or battered childhood red wagon, the spicy scent of your grandfather’s aftershave, the icy sweetness of a wintergreen Lifesaver, the burbling of a mountain creek in winter, or the silky softness of your puppy’s ears – to pique your senses, to evoke your emotions, to paint a picture with words.

.

I stepped away from posting here for a while, to finish what I hope will be the last major revision of my first novel, which I did just days ago.

by D. J. Green | Dec 13, 2017 | Venus & Mars Go Sailing

In my last post, I reflected on moments in nature that felt transcendent to me. I listed many of them, but one, though very much in my mind and heart, I did not, could not, write about. Until now. It’s been a long time coming.

Decades ago, for not-quite three years, I was married to a man who, among his many talents, was a pilot. He owned a much-loved ’53 Cessna 180 and in it we flew to our small weekend getaway, to see his mother in Arizona several times each year from our home in east-central Texas, to geology field trips, down to the Gulf coast where we plane-camped and he fished, and to the New Mexico mountains on the occasional ski weekend.

One late summer day in 1997, flying east, back home from Arizona, while just south of the Guadalupe Mountains of west Texas, in the distance we saw two thunderstorms building. I assumed we would divert around them. But, no, he said, we’d hold our course and scoot right between them. As we approached the darkening storms, the sun and the rain converged in such a way that rainbows formed – one arching above and one swooping below – from the thunderheads on either side. Flying into the heart of the perfect circle made by those rainbows was a deeply transcendent moment in nature.

I have no picture. But in my mind, I hold the picture of those moments – flying into the ring – moments that have come to define my time with the brilliant and adventurous man who was my husband. I can see his blue eyes sparkling, his mischievous smile as turbulence began to jounce us along. And despite the fact that my hands, sweaty with fear, gripped the edge of my seat, and I fought waves of airsickness, I will never forget the gift of flying into that ring, both that particular moment and every moment, even the painful ones, of our marriage.

You might think that I’ve come to idealize this man that I adored, and it’s tempting to do so. But I believe I honor him, and our love, much more by remembering the whole of him. He wasn’t perfect, and in fact, he struggled mightily, particularly with alcoholism. Though he wasn’t in denial of that struggle, privately, he never revealed it publicly. And I feel sure, if he was here now, he would be less than pleased that I’m writing these words and putting them out in the world, perhaps for his friends and colleagues to see. But being with him made me more courageous than I was before, and it’s important to say these words, because alcoholic was not the only person he was. He was an engineering geologist who had worked all over the world, a leader in his profession, a mentor to many young geologists, a professor at Texas A&M University, an avid student of science and history, a lover of music, a photographer, a sailor, a pilot, a son, a father, a grandfather, a friend – and my husband.

Though, in years, he was quite a bit older, in spirit, he moved through, and over, the world with a youthful wonder, curiosity, and boldness that changed the way I have moved through the world myself ever since.

Just a few short months after flying home that day, he perished on a November night, beside his plane, in the Texas hill country. He flew that night, despite the potential for icing conditions, because his students were waiting for him for a weekend field trip. They could have waited. But he did not. I doubt he even considered it.

Just a few short months after flying home that day, he perished on a November night, beside his plane, in the Texas hill country. He flew that night, despite the potential for icing conditions, because his students were waiting for him for a weekend field trip. They could have waited. But he did not. I doubt he even considered it.

And so began the most difficult journey of my life – a month-long search for him, and then a years-long passage through grief.

Now, decades past, I hold the joy of being with him closer than the pain of his loss. I look at the sky this clear New Mexico morning, see the startling blue of his eyes, and feel him with me. I know, in my cells, that love does not die, though the beloved does. And I am most grateful for flying into the ring.

On this day, twenty years ago, Norman Ross Tilford’s body and his plane, were found by a hunter deep in the Texas hill country.

To the family, friends, colleagues, and Civil Air Patrol pilots who searched for him with me – you will always have my heartfelt thanks.

by D. J. Green | Nov 28, 2017 | Ground Work

Totality – it’s the word used to describe the one minute and fifty-four seconds during which I witnessed the moon completely covering the sun on August 21, 2017, as a total solar eclipse swept across North America.

I would also call it transcendence.

I hope those 114 seconds, and the many minutes before and after as the moon moved across the sun and then moved on, will live in my memory as long as I do.

Totality – a time like sunrise or sunset, but on the entire 360 degrees of horizon, not just in the east or west. A time when the birds went silent. A brief, hushed, stunning interval to behold the sun’s corona high in the sky. And then when those seconds ticked away, and the sun flashed its ‘diamond ring’ as the moon continued on its path, the birds burst into wild song, a chorus that went on and on as if they too were celebrating the transcendence of the moment.

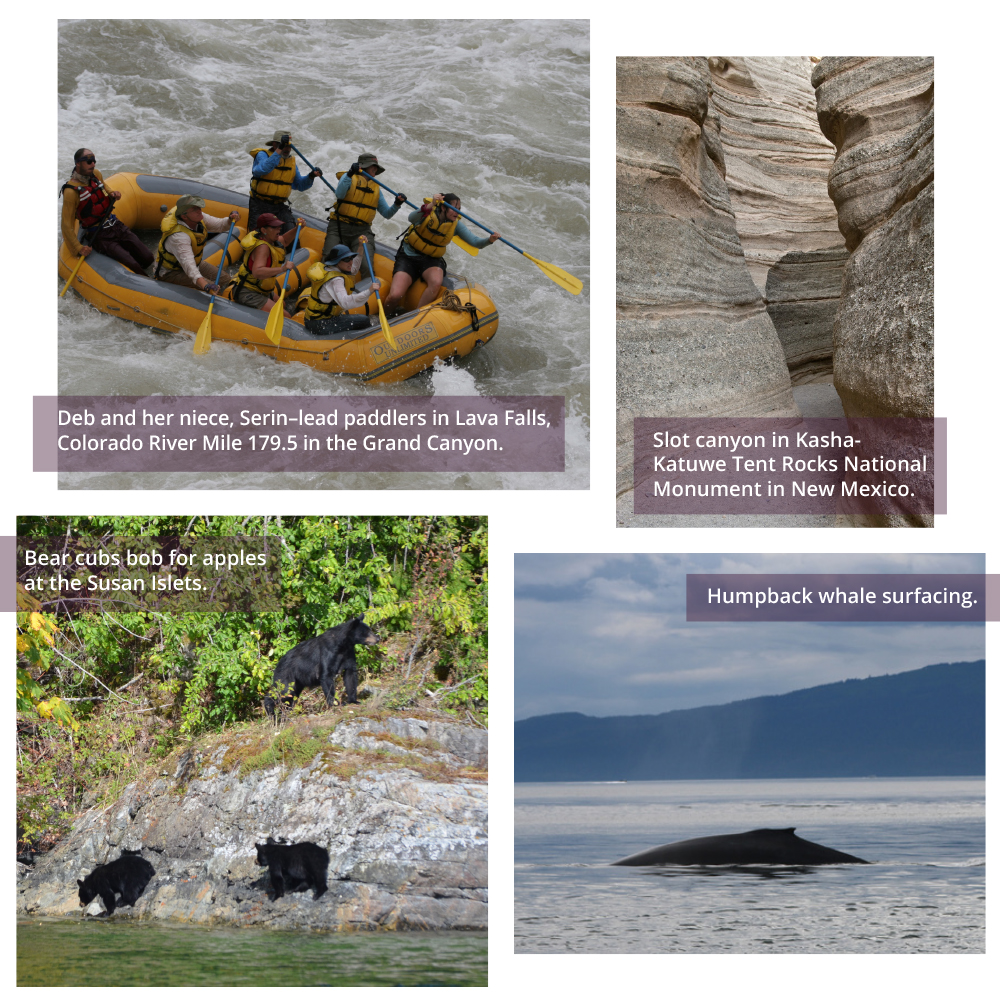

I find most of my moments of transcendence in nature – the eclipse, for one. But so many more – like dark starry nights in the wide open west, finding 300 million year old marine fossils on a mountaintop while hiking, being awash in the icy rapids of the Colorado River deep in the Grand Canyon, thunder rumbling down the canyon while a distant storm puts on a light show like no other, placing the palms of my hands on each side of a slot canyon carved in tuff deposited by a volcanic eruption more than a million years ago, moving with the wind on the fair Kagán, watching bear cubs shake apples from a tree to their mama on a nearby shore, bioluminescence sparkling off my oars as I row the dinghy at night, and always when I see dolphins or porpoises or whales, or even hear their breathy blows in the distance.

I’ve been lucky to attend transcendent moments in nature both on my own and in the company of those I love. On my own, I savor the feeling of my smallness, both in space and time, in the passing scene of this magnificent planet. And with others, I delight in the shared experience, and the shared appreciation of that experience.

Those moments outside make me strong inside. And then I go inside….

These days, when I go back inside – I pick up my phone and call my congresswoman and senators, I sign petition after petition, and I volunteer time with and write checks to organizations that will help keep our wild places wild and accessible, not only to me, but to those who may not have had transcendent moments in nature yet. And in doing so, I hope I will help others have precious moments to carry in their hearts and memories.

In this season, when we pause to reflect on what we’re thankful for, I hope you will go outside – gaze upon the waxing moon as it rises, hold the splendor of an autumn-crimson maple leaf, or pick up a rock and feel the Earth’s long history in the palm of your hand – and embrace the transcendence, the totality.

From my home at the base of the Sandia Mountains to the beautiful old Mabel Dodge Luhan House at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in Taos, I drove for miles alongside the Rio Grande as the road climbed from Española into the gorge of the river that flows from a source high in Colorado’s Southern Rockies to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico. It rippled over basalt boulders that had tumbled into its bed from the steep slopes above. Winter bare cottonwoods revealed their convoluted forms, another of nature’s graceful sculptures. Light glinted off the faces of boulders burnished with desert varnish. I imagined the music of the river, a constant murmur, overshadowed that day by the whoosh of the wind, whose gusts the soaring crows danced upon, riding waves of air. I could drive this stretch of road every day, and still it would inspire my awe.

From my home at the base of the Sandia Mountains to the beautiful old Mabel Dodge Luhan House at the base of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in Taos, I drove for miles alongside the Rio Grande as the road climbed from Española into the gorge of the river that flows from a source high in Colorado’s Southern Rockies to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico. It rippled over basalt boulders that had tumbled into its bed from the steep slopes above. Winter bare cottonwoods revealed their convoluted forms, another of nature’s graceful sculptures. Light glinted off the faces of boulders burnished with desert varnish. I imagined the music of the river, a constant murmur, overshadowed that day by the whoosh of the wind, whose gusts the soaring crows danced upon, riding waves of air. I could drive this stretch of road every day, and still it would inspire my awe. Nearly every day (yes, sometimes I forget), I walk in gratitude to live in places were nature is so reachable. I can touch the paper thin wisp of a seed pod. I can hear it rattle in the breeze. I can watch a lizard no bigger than my pinky finger scurry into the protective spines of a prickly pear’s paddles. I hear the coyotes’ howls echoing through arroyos, their pups’ yips and yaps new voices in nature’s song. But even in the city, there is birdsong, the rustle of bare trees’ branches in the wind, and the occasional passing of a coyote. Wherever I am, I can find it – awe – if I remember to look, to listen.

Nearly every day (yes, sometimes I forget), I walk in gratitude to live in places were nature is so reachable. I can touch the paper thin wisp of a seed pod. I can hear it rattle in the breeze. I can watch a lizard no bigger than my pinky finger scurry into the protective spines of a prickly pear’s paddles. I hear the coyotes’ howls echoing through arroyos, their pups’ yips and yaps new voices in nature’s song. But even in the city, there is birdsong, the rustle of bare trees’ branches in the wind, and the occasional passing of a coyote. Wherever I am, I can find it – awe – if I remember to look, to listen. The next morning, I woke to the hush that blankets the landscape with even a dusting of snow. Always a blessing in the desert, this winter any moisture is a particular gift given the parched season we’ve had. I scooped up a handful, and as I lifted it to contemplate the intricacies of the delicate flakes, the sun peeked through a cloud break and shone over my shoulder. Nature’s wonder sparkled there, right in the palm of my hand.

The next morning, I woke to the hush that blankets the landscape with even a dusting of snow. Always a blessing in the desert, this winter any moisture is a particular gift given the parched season we’ve had. I scooped up a handful, and as I lifted it to contemplate the intricacies of the delicate flakes, the sun peeked through a cloud break and shone over my shoulder. Nature’s wonder sparkled there, right in the palm of my hand.

Recent Comments