by D. J. Green | Apr 21, 2017 | Ground Work

[vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]For me, if something’s worth doing, it’s worth learning to do it well. And that means going to school, perhaps in a traditional way, perhaps not.

Schooling

I didn’t walk out of high school and into my professional life as a geologist. I went to school for six years. I studied in classrooms and labs. I tromped the Tobacco Root Mountains of Montana in field camp, and took field trips to diverse geologic terrains from the Adirondacks to the submarine canyons of St. Croix. Then I went to work, where in addition to learning the science, I was schooled in how to plan and implement a site investigation, how to interpret the collected data, how to draw maps and cross-sections that communicated that data best, and how to write a report that told a project’s story effectively. I apprenticed myself to excellent geologists and project managers. I learned my trade.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”405″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_single_image image=”406″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

A New Trade?

I’ve always been an avid reader, I grew up in a house filled with books, and it took. I love to be transported by story, to landscapes and into emotions I’ve never known, and back to those I have. But when I sat down to write my first story, and then read the draft, yikes. It was clear to me there was much more to writing than just having a story to tell. Everyone has stories worth telling, but that doesn’t make everyone a writer. It was time to go to school again. But…I admit it was uncomfortable to be a novice, to not even know where to start. I had reached a certain age and level of competence at work, and in life. Was I really willing to not know how? Though I said I wanted to learn new things all through life, it was harder to step out of my comfort zone and do it.

Inspiration

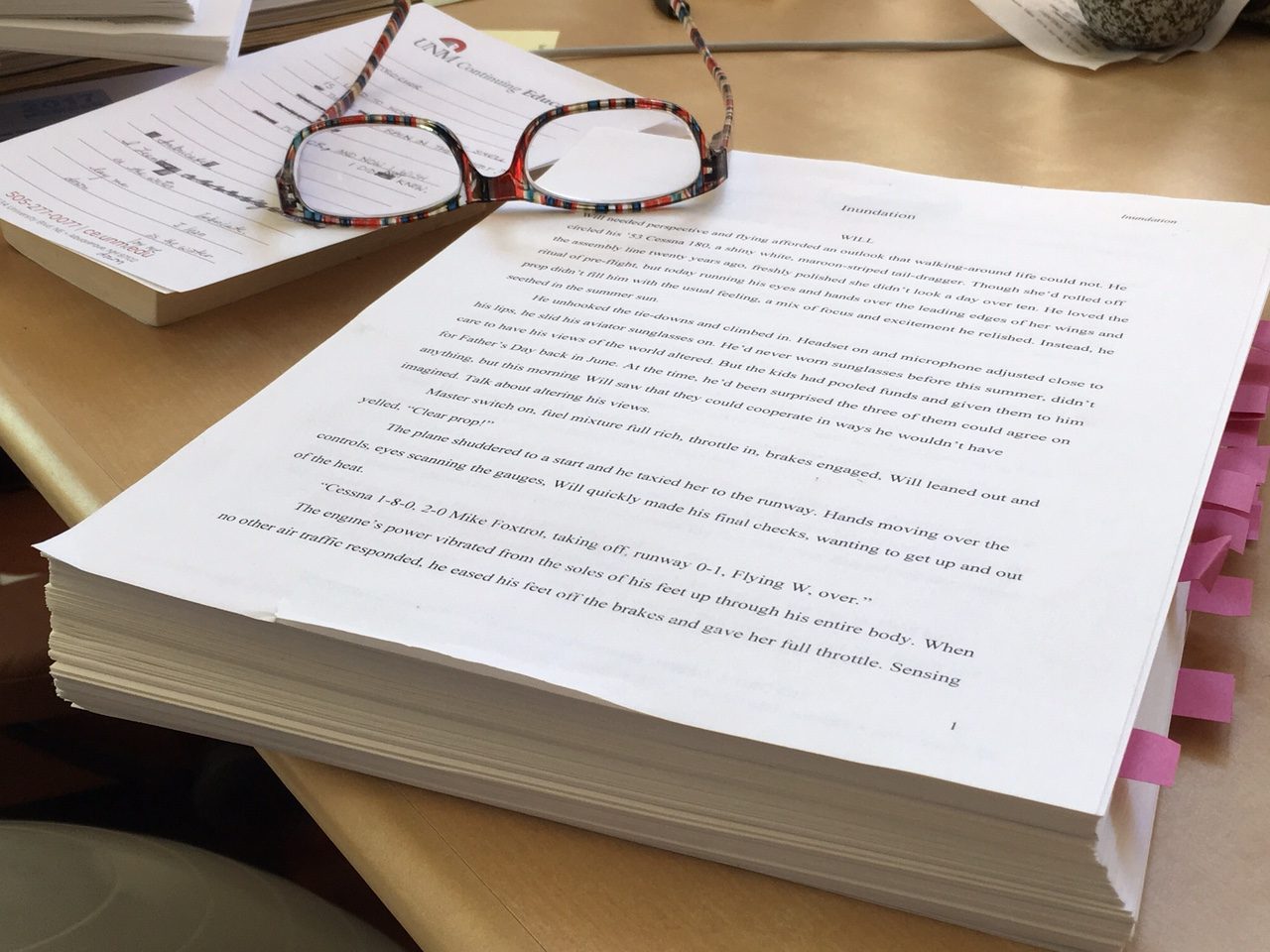

Jerry skiing at Jackson Hole, Wyoming

Then another mentor came into my life – my late partner, Jerry. Not a natural athlete, and also of a certain age and level of competence in life, he took on learning to ski at 60. Both downhill and cross-country. He took lessons. He read and analyzed. And he practiced, taking joy in that work, celebrating his progression from green to blue to black slopes. It was inspiring. If Jerry could do it, learn something so outside his comfort zone and love the process, so could I.

I chose a non-traditional route for my education in writing, since spending months on field projects for work didn’t lend itself to a classroom schedule. I took classes at the Iowa Summer Writing Festival and the Taos Summer Writers’ Conference, I took online classes, and I studied authors I admire by reading and reading and reading. I learned to read as a writer. How did that author make me laugh? Or cry? I spent one summer re-acquainting myself with grammar, studying Sin and Syntax and Eats, Shoots & Leaves. And I practiced what I learned over and over, not unlike Jerry’s determined turns down the slopes. I still do.

It took years of my writing apprenticeship to find the story I needed to tell, then nine years and more drafts than I can count to tell it. Have I learned my craft well enough that readers will want to inhabit the world I’ve built with words and become acquainted with the characters who live in it? Again, I’ll have to step outside my comfort zone to find out. But like Jerry, I can push off the lip atop the slope and make the first turn.

.

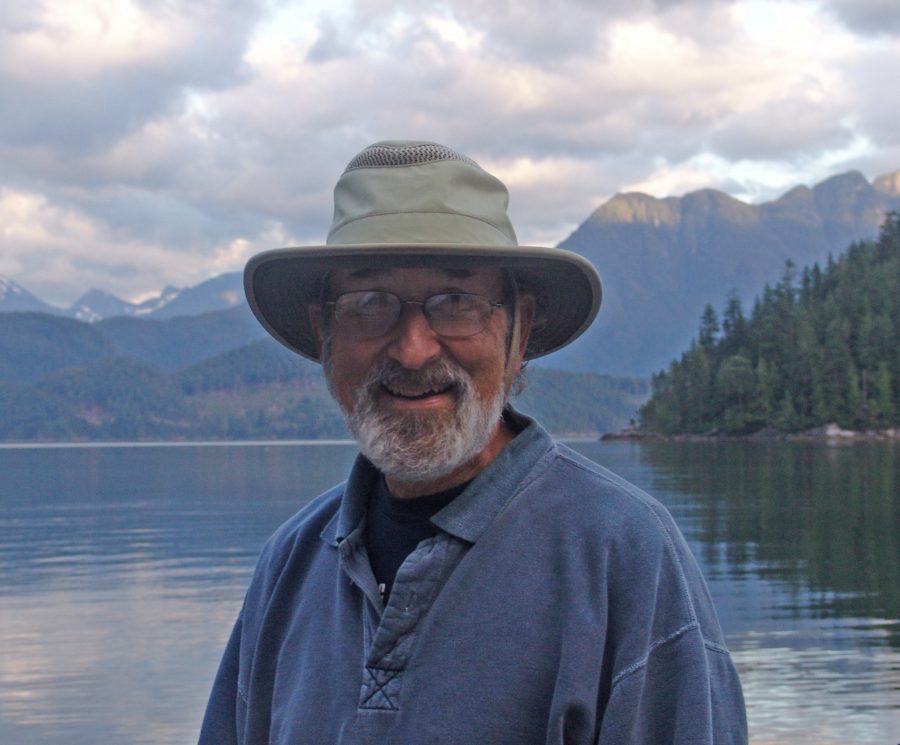

Jerry at his most beloved cruising spot, near Toba Inlet in BC

.

.

This post is dedicated to Jerry Blakely – a wonderful mentor, devoted friend, and kind and generous man, who died four years ago today.

by D. J. Green | Mar 8, 2017 | Ground Work

I thought I was going to write about blue today, but it’s going to be sky blue pink with yellow polka dots instead.

When I was a kid, if you asked my dad what his favorite color was, sky blue pink with yellow polka dots was his answer. Maybe that gives you a sense of what he could be like. Let’s just say that my family often put the fun in dysfunctional.

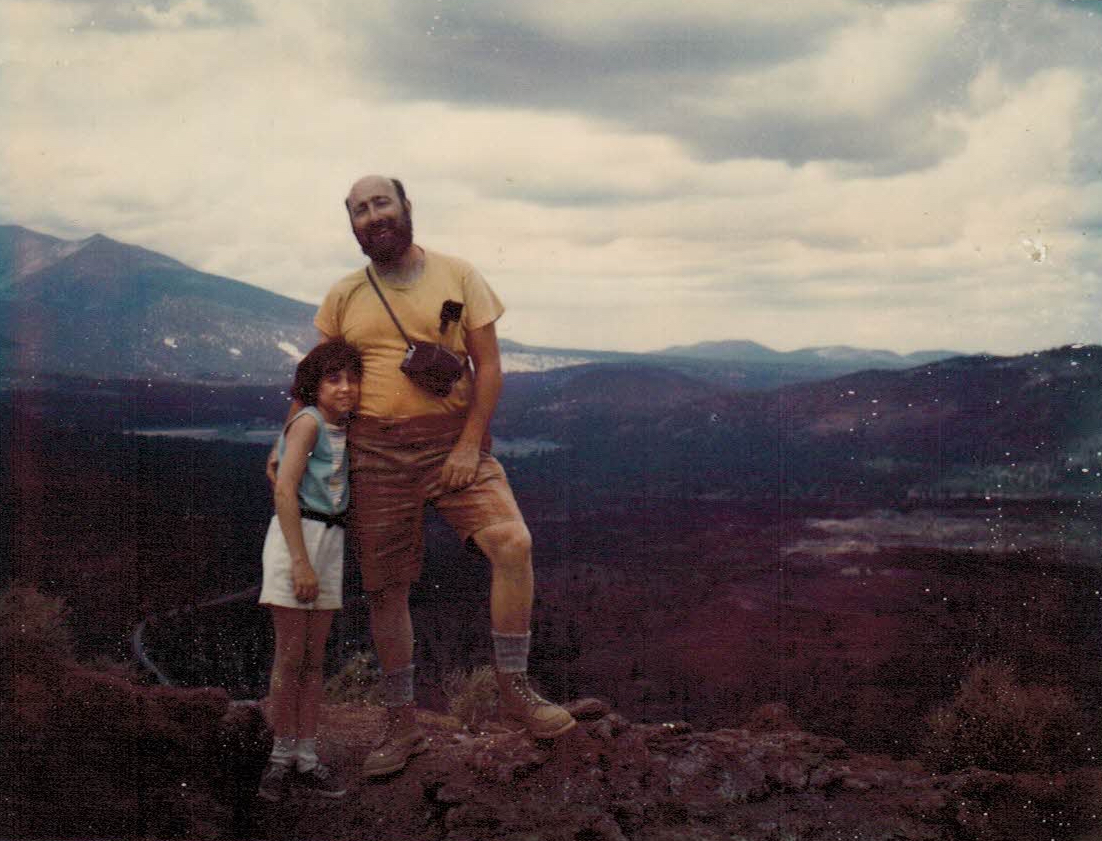

Chip off the old rock? Deb with her Earth Science teacher dad at the top of Sunset Crater Volcano in Arizona, Summer 196?. Photo taken by a kind fellow hiker with a Polaroid camera.

Dad, Summer 1975

This starts with blue and that’s fitting, because that’s how I feel. My father will be evaluated for hospice care tomorrow. This is not wholly unexpected, he’s 95, and in the late stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. His disease has progressed with long periods of stability punctuated with precipitous declines. A few days ago, he began to slide after more than a year of somewhat steady state. It’s not unlike Stephen Jay Gould’s famous (among paleontologists, at least) theory of punctuated equilibrium in evolution. But rather than evolving, my father’s life and being have devolved in this way. As an Earth Science teacher, long before the depths of Alzheimer’s, I think Dad would have found that metaphor interesting. Given the starting point of this decline, it’s hard not to think it his last.

As I so often do when I feel blue, I walked. With little Capi in my backpack and Sandy by my side, I ventured from home into the desert. Today, the path before me recalled so many others. And my first hiking companion, my father. We hiked up Sunset Crater Volcano in Arizona, to the top of Lassen Peak in California, we wandered the Black Hills of South Dakota, he explained stalactites and stalagmites at Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, and with me holding tight to the back of his belt where the trail was too narrow for us to walk side by side, we scaled the heights of Angels Landing in Utah. I am who I am and love what I love in no small part because of who he is and what he loves.

As I so often do when I feel blue, I walked. With little Capi in my backpack and Sandy by my side, I ventured from home into the desert. Today, the path before me recalled so many others. And my first hiking companion, my father. We hiked up Sunset Crater Volcano in Arizona, to the top of Lassen Peak in California, we wandered the Black Hills of South Dakota, he explained stalactites and stalagmites at Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, and with me holding tight to the back of his belt where the trail was too narrow for us to walk side by side, we scaled the heights of Angels Landing in Utah. I am who I am and love what I love in no small part because of who he is and what he loves.

Like so many winter mornings, a flock of mountain bluebirds rose from the first junipers the dogs and I passed, evoking a memory of my first birdwatching buddy. Dad, of course. What a contrast the Saturday morning bird walks in the woods of Staten Island are to my desert morning bird walks now. And as I was thinking that, a raven flew so close I could feel its wingbeats move the air.

Like so many winter mornings, a flock of mountain bluebirds rose from the first junipers the dogs and I passed, evoking a memory of my first birdwatching buddy. Dad, of course. What a contrast the Saturday morning bird walks in the woods of Staten Island are to my desert morning bird walks now. And as I was thinking that, a raven flew so close I could feel its wingbeats move the air.

The breeze freshened, ruffling Sandy’s fur, and he waved his lovely plume of a tail. He ambled back to me and nudged my hand with his wet black nose.

“I guess there are worse things than being blue,” I said to him, and one of the mountain bluebirds agreed. Perched atop a juniper, he sang.

“Life isn’t always easy,” he seemed to say, hanging onto his branch in the wind, “but it is sweet.”

Not just sweet, sky blue pink with yellow polka dots sweet.

Note: I will be working on a deadline for the revision of my novel over the next weeks. I’ll be back here with you in April. Stay tuned, everyone! Thanks, Deb

by D. J. Green | Feb 22, 2017 | Ground Work

Cathy on the trail with the inner gorge in the lower background

Sometimes I don’t hold the rock, it holds me. Some rocks don’t get stuffed into a pocket, then put on a shelf. Sometimes I nestle into a nook where I fit as well as a rock might fit in my hand, and make a memory to hold. Last October, backpacking into the inner gorge of the Grand Canyon (where the myriad rocks are oh-so-tempting, but I only take pictures and only leave footprints) was one of those times.

I went with my friend, Cathy. She yearned to experience the canyon, a place she’s described as her inner landscape, though she’d never seen it except in photographs before. To witness her eyes widening at her first look over the rim into and across the canyon, was one of the best views (and that’s saying something) of the trip for me. Then we swung our 35+ pound packs of gear and food and water on and began the descent. We shared 5 amazing days of hiking, exploring, discovering, and being. She even let me go on and on about the geology, from the scale of a bit of mica to the deposition of the formations into which the canyon is carved.

Cathy finds a bit of biotite mica

After settling into camp on the fourth day, I scrambled up a wall of Vishnu Schist and Zoroaster Granite. The rocks of the Vishnu Formation, predominantly mica schists, are the oldest in the Grand Canyon. Approximately 2 billion years ago, 25,000 feet of sediments were deposited and volcanics extruded onto the ancient sea floor. During an orogeny, a mountain-building episode, 1.7 billion years ago, those rocks were folded, faulted, and uplifted (metamorphosed), and intruded by the Zoroaster Formation, predominantly granite (also subsequently metamorphosed to form granite gneiss). The resulting mountain range is believed to have been 5-6 miles high. Over the next 500 million years, the mountains were eroded until only their roots remained, and today, the roots of those mountains form the steep walls of the inner gorge.

Geologist learn to think in terms of hundreds of millions of years, thousands of feet of sediment being deposited, and mountains being uplifted by miles pretty casually. But understanding the processes that shape the earth makes them no less awesome, perhaps even more so, and that last evening in the canyon, I mused on the rocks’ age and beauty from a big-enough-just-for-me ledge.

The next morning at dawn, Cathy and I began our hike out, 7 steep miles from the river to the rim on the South Kaibab Trail. We climbed through 2 billion years of geologic time and a place of such splendor and complexity that I will never know it all, no matter how often I explore it. And maybe that’s the point, I can never know it all. But I can always learn, wonder, and wander, and almost always find the perfect rock to hold me for a while.

.

Tell me, what sparks your wonder?

by D. J. Green | Feb 3, 2017 | Venus & Mars Go Sailing

Kagán is a bluewater cruiser, a stout and seaworthy sailboat. If we, her crew, are prepared and courageous enough, she can take us around the world. The sailing instructor who gave me the know-how and instilled me with the confidence to singlehand Kagán when I took the helm as skipper, spoke about boats like Kagán as magic carpets. And she ought to know, she sailed hers around the world twice!

.

Deb fixing the anchor light

The lure of that magic has sailed through my mind and heart for years. Not that I’ve romanticized what full-time sailing would be like, though it is tempting to do so I’ve fixed too many leaky hoses, changed too many joker valves (part of the head assembly, yuck), spent too many hours waxing and polishing, and changed the bulb in the anchor light (which happens to be at the top of the mast) too many times to do that. But the self-sufficiency an ocean crossing would require, the courage it would demand, and the awe it would inspire intrigues me. Just imagine standing watch on a clear night when the moon is new and no light pollution from horizon to horizon – only the stars in the sky and the bioluminescence in your wake. Sailors often use terms that invoke flights of fancy – we fly spinnakers in light airs and we sail wing-on-wing on downwind runs.

Kagán sailing wing-on-wing south of Dodd Narrows

But these days, the flight of fancy that crosses my mind most is steering a heading toward a destination that hasn’t lost its moral compass, and concerning myself with trade winds not trade wars. Casting off the dock lines for a faraway port would leave me too busy to follow the news on a minute-by-minute basis, even if technology could keep me connected. Instead I’d be setting sails and standing watches and fixing what breaks (because Kagán, as stout as she is, is a complex piece of equipment afloat in a corrosive medium whose motion is ceaseless and powerful).

.

But here on land, there are values and people and landscapes I hold dear. So my decision, at least for now, is to stay grounded and try to fix what feels broken here, knowing there’s a magic carpet I can climb onto and sail away someday if I choose.

by D. J. Green | Jan 16, 2017 | Ground Work

Waking before dawn with today’s to-do’s scrolling through my mind, I felt choked up just brewing a cup of tea – compile tax info, update Dad’s expenses, call the accountant, brush the dog, vacuum up the dog hair, do the laundry, work a closing shift at the bookstore, and oh yes, how’s the re-write of that novel I’ve been working on for years going….

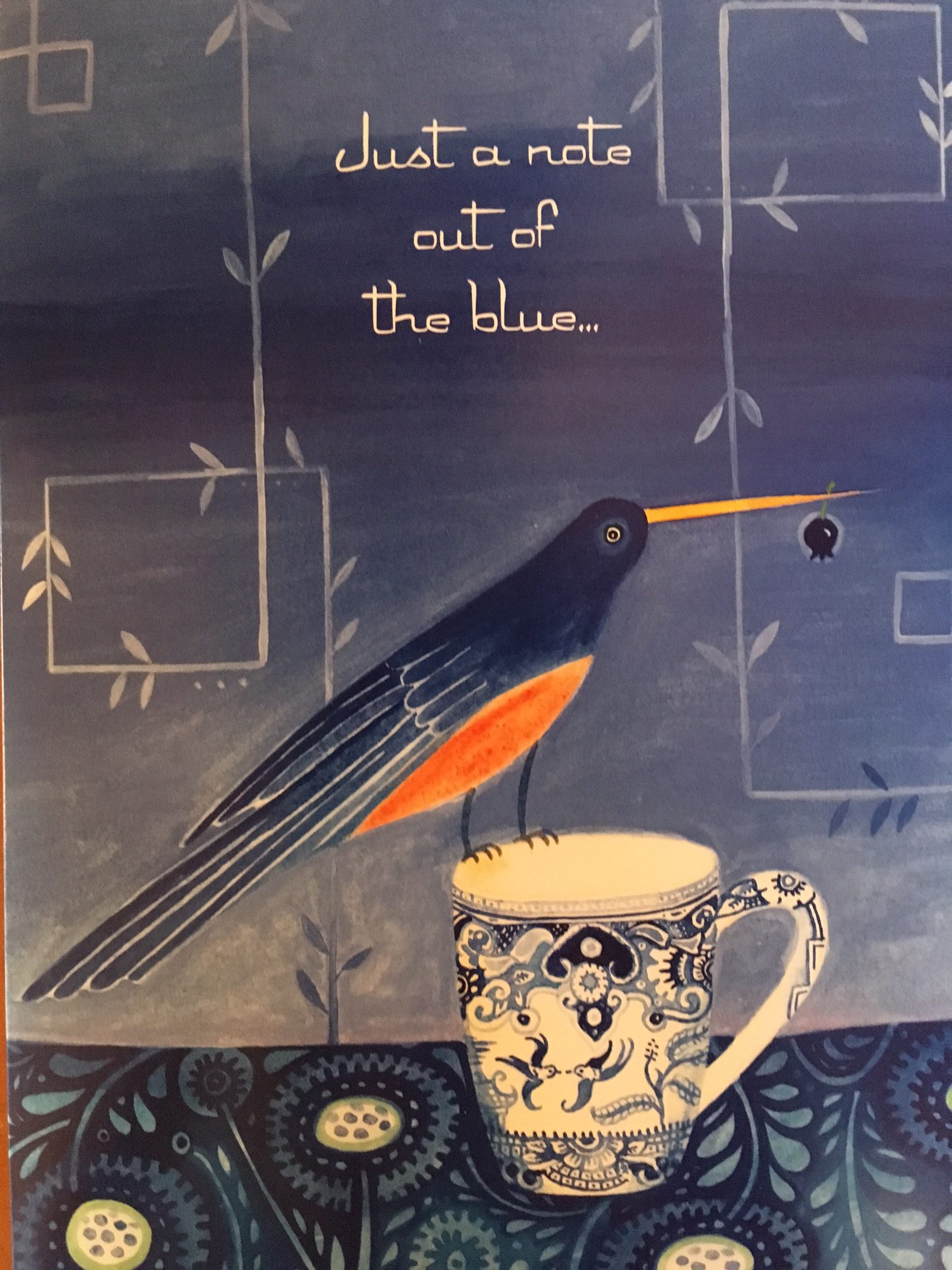

I drank my tea, trying to swallow the anxiety spawned by the news and to-do’s along with it. Then Sandy and I headed out for our walk. He led me up the trail at sunrise, his fur ruffling in the chill breeze, his too-small-for-his-body ears bouncing with each step. A flock of Mountain Bluebirds, wintering in the junipers, took to the sky as we passed, the incredible color of their feathers flashing.

I drank my tea, trying to swallow the anxiety spawned by the news and to-do’s along with it. Then Sandy and I headed out for our walk. He led me up the trail at sunrise, his fur ruffling in the chill breeze, his too-small-for-his-body ears bouncing with each step. A flock of Mountain Bluebirds, wintering in the junipers, took to the sky as we passed, the incredible color of their feathers flashing.

The Sandia Mountains tower 5,000 feet above our mile-high home, and we walk in their shadow. The banded uppermost layer is 300 million-year-old Madera Limestone, deposited in an ancient sea where crinoids and brachiopods and bryozoans flourished (creatures that still inhabit our oceans today, though in different forms). But the range is dominated by the Sandia Granite, a 1.4 billion-year-old formation (yes, billion!). Its reddish pink orthoclase feldspar crystals make the mountains glow, gold shading to deep pink, as the sun angle lowers late in the day,  giving the range its nickname – the Watermelon Mountains.

giving the range its nickname – the Watermelon Mountains.

The views – of a billion years of time and thousands of feet of displacement on the faults that form the Rio Grande Valley – remind me to lighten up; my whole lifetime is less than a snap of the fingers in the story of this landscape. My ashes will one day be scattered in the arroyo beside my house, and I will be carried to the river and beyond. My adobe house will melt back into the earth, leaving hardly a trace for whoever or whatever inhabits this space down the track of geologic time.

Politics won’t matter. Money won’t matter. The stuff by which we define success, or failure, won’t matter. I don’t have to take life, and myself, so seriously. I’m free to explore and take chances. I can stand up for what matters to me, without thinking that one way or the other it’s the end of the world. Geologic time proves to me it won’t be.

When I remember to live like that, in addition to having the courage to try, whether I succeed or fail, there’s also space to savor the finger snaps of my own lifetime – a walk with my beloved dog, making tracks in fresh snow, Sirius sparkling in a black velvet sky, Wynton Marsalis playing Where or When, a hawk soaring overhead, reading Mary Oliver’s Wild Geese, and the glint of a mountain moonrise. In those moments, my heart fills with gratitude – it feels physical, like my heart is actually swelling in my chest. Have you ever felt it?

When I remember to live like that, in addition to having the courage to try, whether I succeed or fail, there’s also space to savor the finger snaps of my own lifetime – a walk with my beloved dog, making tracks in fresh snow, Sirius sparkling in a black velvet sky, Wynton Marsalis playing Where or When, a hawk soaring overhead, reading Mary Oliver’s Wild Geese, and the glint of a mountain moonrise. In those moments, my heart fills with gratitude – it feels physical, like my heart is actually swelling in my chest. Have you ever felt it?

I can’t imagine it being expressed any better than Oliver Sacks did in one of his last essays, My Own Life, “Above all, I have been a sentient being, a thinking animal, on this beautiful planet, and that in itself has been an enormous privilege and adventure.”

Recent Comments