by D. J. Green | Jul 28, 2018 | Ground Work, Venus & Mars Go Sailing

In the San Juan Islands of Washington state, there are many lovely anchorages to drop a hook. Some would say Sucia Island is one of the loveliest. Part of a three-island marine state park, it has trails, campsites, mooring buoys, and anchoring room galore. It’s also a great playground for a geologist.

The horseshoe shape of the island tells part of its geologic history; sedimentary strata, which were originally flat-lying, underwent tectonic compression shaping first a syncline (a big U-shaped fold), then further compressive forces tilted it forming what geologists call a plunging syncline, and what sailors call the big, beautiful anchorage of Echo Bay.

.

But it’s the striking sculpted sandstone cliffs that draw so many to Sucia. The “carving” that looks like intricate modern art is known as honeycomb weathering, for obvious reasons. Three specific conditions are needed for this type of weathering to occur: soluble salt, as in seawater; porous rock, like the Chuckanut Sandstone which comprises most of the bedrock on Sucia Island; and alternating cycles of wetting and drying, as in tides flooding and ebbing.

The Chuckanut Formation sediments were deposited by a meandering river 50 million years ago. There were several depositional environments along the river, including braided streams, point bars, and oxbow lakes, resulting in numerous rock types within the formation – conglomerates to sandstones to siltstones.

The Chuckanut Formation sediments were deposited by a meandering river 50 million years ago. There were several depositional environments along the river, including braided streams, point bars, and oxbow lakes, resulting in numerous rock types within the formation – conglomerates to sandstones to siltstones.

To create the intricate weathering pattern, seawater is absorbed into the porous sandstone, then evaporation causes expanding salt crystals to wedge sand grains apart. As cavities develop, microscopic algae find a sheltered environment in which they can thrive on the walls of the cavities. The coating of algae slows weathering on the side walls, so the divots deepen, making the honeycombs more and more dramatic. Understanding how these sculpted sandstones form, makes me appreciate their beauty all the more.

.

Showing signs of weathering myself, I can’t resist the metaphor of time and erosion sculpting us into more beautiful shapes than we were before.

What metaphors resonate for you?

Notes:

- To learn more about the geology of Sucia Island, there’s a short paper, “Sucia Island, The Geologic Story” by George Mustoe of Western Washington University (April 2008) that’s very informative.

- Special thanks to Judi Pringle for kayaking Sucia Island with me, where I took the pictures for this post.

by D. J. Green | Jun 29, 2018 | Venus & Mars Go Sailing

“Don’t you get bored?” a coworker on a field job asked. “Just sitting on a boat all summer?”

Clearly he had never owned or lived on a boat. There’s never nothing to do. “Just sitting” only happens at the risk of enduring substantial guilt, induced by the as-yet unaddressed items on the to do list.

Our sailboat is like a very compact house, equipped with complex electrical, plumbing, and propulsion systems. It floats in a corrosive medium (we sail the Salish Sea, which is, of course, saltwater) that is always moving, sometimes gently and sometimes not. That means there’s almost always something to fix, despite keeping up with regular maintenance. Then there’s the polishing. And decks to be swabbed. Really, that’s not merely a phrase. No, I don’t get bored.

One of the things I love about life on Kagán, is that much of the work is physical. It often has a meditative quality to it. Wax on, wax off is also not simply a phrase. A week ago, we finished varnishing the bright work (that’s nautical for wood trim). The next day, I waxed the gelcoat in the cockpit. When it rained, I reveled in seeing the droplets beading on the newly-protected teak. And as I write this, the gelcoat is gleaming in the sun. The pleasure of seeing those results is worth all the hours it took to get them. I believe if we take care of Kagán, she’ll take care of us. Keeping her beautiful is one of the ways we do that.

One of the things I love about life on Kagán, is that much of the work is physical. It often has a meditative quality to it. Wax on, wax off is also not simply a phrase. A week ago, we finished varnishing the bright work (that’s nautical for wood trim). The next day, I waxed the gelcoat in the cockpit. When it rained, I reveled in seeing the droplets beading on the newly-protected teak. And as I write this, the gelcoat is gleaming in the sun. The pleasure of seeing those results is worth all the hours it took to get them. I believe if we take care of Kagán, she’ll take care of us. Keeping her beautiful is one of the ways we do that.

But it’s not all scrubbing and polishing, I’m also engaged intellectually during our summers on Kagán. I think I do more basic math here than in land-based life. I calculate tide fluctuations to determine anchor rode lengths and evaluate current directions, speeds, and timing for transiting narrow passages. There’s also the decision making involved in planning for and executing cruises of several weeks, like water use management and provisioning. And then there are the minute-to-minute judgements while under sail – what tack to take, and how to trim the sails for speed and comfort and, of course, safety.

But it’s not all scrubbing and polishing, I’m also engaged intellectually during our summers on Kagán. I think I do more basic math here than in land-based life. I calculate tide fluctuations to determine anchor rode lengths and evaluate current directions, speeds, and timing for transiting narrow passages. There’s also the decision making involved in planning for and executing cruises of several weeks, like water use management and provisioning. And then there are the minute-to-minute judgements while under sail – what tack to take, and how to trim the sails for speed and comfort and, of course, safety.

The outcome of a job, the consequence of a choice is often immediate and tangible on Kagán – it’s a stark contrast to so much of the online and virtual work we currently do.

We’re at anchor today, and I’m “just sitting” in the cockpit at the moment. But in addition to admiring the very shiny gelcoat, I’m listening to oystercatchers chatter on the rocky shore, savoring the cool breeze as Kagán swings to it, and following the kee-kee-kee call of a bald eagle to see it swooping in for a landing on a high snag. Peaceful, happy, and offline, yes. Bored, no.

Tell me, what engages you?

by D. J. Green | Jun 9, 2018 | Ground Work

Last week, I wrote about two disciplines I practice on a regular basis, and how they’ve helped me “become what I practice.” Today, I’ll explore two more.

Engine Checks:

Although Kagán is a sailboat, the wind doesn’t always blow, nor am I expert enough to maneuver under sail in tight spaces like into and out of marinas, so the auxiliary engine (a 37-horsepower marine diesel) is essential to our cruising life. At least every 10 hours of running time, we do an engine check – checking the engine oil and coolant levels, feeling the tension on the fan belt to the alternator, and taking a good long look for drips from the myriad hoses snaking through the engine. Though it doesn’t take much time, it’s a bit of a production – moving the companionway ladder, lifting off the forward engine cover, and crouching on hands and knees with a flashlight, reading glasses, and paper towels.

Although Kagán is a sailboat, the wind doesn’t always blow, nor am I expert enough to maneuver under sail in tight spaces like into and out of marinas, so the auxiliary engine (a 37-horsepower marine diesel) is essential to our cruising life. At least every 10 hours of running time, we do an engine check – checking the engine oil and coolant levels, feeling the tension on the fan belt to the alternator, and taking a good long look for drips from the myriad hoses snaking through the engine. Though it doesn’t take much time, it’s a bit of a production – moving the companionway ladder, lifting off the forward engine cover, and crouching on hands and knees with a flashlight, reading glasses, and paper towels.

When everything is working well day after day, we begin to wonder if it needs to be done so frequently. But little changes can mean a lot. As our sailing season wound down last year, we noticed some pinkish ooze on one side of the fresh water/coolant pump. We wiped it off and monitored it. On our very last morning at anchor, it was my turn to do the engine check. The pink goo on the pump seemed thicker and there were dribbles on the absorbent pad below it, but there was plenty of coolant in the reservoir. We decided we were good to go back to our home marina just a few hours away, but I made a note in Kagán’s log and called our mechanic as soon as we were snug in our slip.

Turns out the casting of the pump housing was porous, and the pump needed to be replaced. By doing our engine checks almost every day, we caught what could have been a big problem before it was a problem at all. I count that as a little discipline with a big payoff.

Releasing Attachment to Outcomes:

I was introduced to the concept of undertaking something I cared about, then releasing attachment to its outcome eight years ago when I was diagnosed with breast cancer and began the weeks of testing to learn more about what I would be dealing with – what type of cancer, what stage, and if/where it had spread. In a case like cancer, it’s especially hard to release the desire that the outcome be favorable. But it was a worthy effort to make. Getting educated and assembling the best medical team possible was important, and so was striving to be peaceful with whatever was in store for me.

I was lucky. The disease was in an early stage, and the surgery and radiation treatments, though not easy to get through, left me cancer-free and able to resume a lifestyle that restored my health fully. It may seem odd, but looking at it through the prism of years, I think the experience actually enhanced my happiness as I feel deep gratitude for how well and strong I am.

The discipline of releasing attachment to outcomes is one that I continue to practice, though imperfectly. I try to do my best simply for the sake of doing my best, rather than to achieve a specific result – like completing a well-written novel, not knowing if I’ll succeed in publishing it and being diligent in maintaining Kagán’s safety and mechanical systems, despite the inevitability of breakdowns. And then there’s attending to my health, though there are no guarantees that the cancer won’t recur, and there is the guarantee that aging will take its toll – so, walking, biking, doing yoga, and those daily sit-ups and push-ups need to be about feeling good on any given day, without attachment to the days that follow.

This discipline is one I haven’t quite become. All too often I am attached to what I perceive as a good outcome. But I keep practicing.

What are the disciplines you find most challenging, and why?

by D. J. Green | Jun 3, 2018 | Ground Work

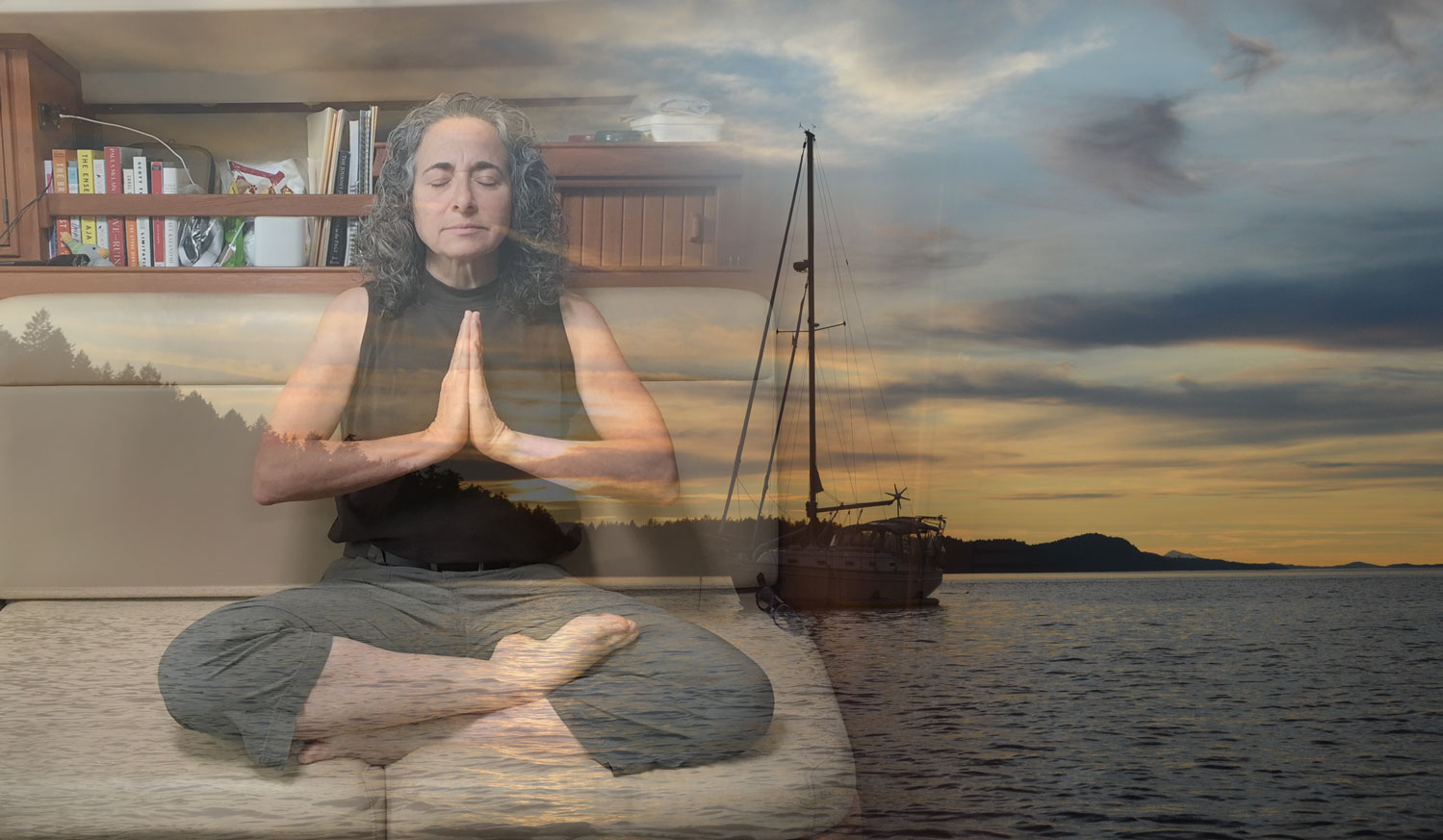

One of my many teachers of writing or yoga or life, said to me, “You become what you practice.” I’ve never forgotten the phrase, and I believe it. There are several little disciplines I practice, and today I’ll talk about two of them.

Sit-ups and Push-ups:

I can’t remember when I began doing sit-ups and push-ups every day. It’s been decades. The only time I haven’t done them for any length of time was when I had surgery and radiation treatments for breast cancer eight years ago. Since radiation really saps your energy, it was months before I felt strong enough to consider starting them up again, or not. I recalled a conversation I’d had years before with a friend in her fifties, we were sharing a hotel room and she commented on my daily routine, saying she used to have a similar one, until she’d turned fifty…and then she gave it up. I also remembered thinking that I wouldn’t make the same choice. I’m okay with getting older, but I’m not so okay with getting weaker, to the extent that I have control over it. So, there I was – just turned fifty myself and a newly-minted cancer survivor – making a decision to keep or let go of a small, daily discipline that could help me maintain strength and fitness. I decided to keep it.

I can’t remember when I began doing sit-ups and push-ups every day. It’s been decades. The only time I haven’t done them for any length of time was when I had surgery and radiation treatments for breast cancer eight years ago. Since radiation really saps your energy, it was months before I felt strong enough to consider starting them up again, or not. I recalled a conversation I’d had years before with a friend in her fifties, we were sharing a hotel room and she commented on my daily routine, saying she used to have a similar one, until she’d turned fifty…and then she gave it up. I also remembered thinking that I wouldn’t make the same choice. I’m okay with getting older, but I’m not so okay with getting weaker, to the extent that I have control over it. So, there I was – just turned fifty myself and a newly-minted cancer survivor – making a decision to keep or let go of a small, daily discipline that could help me maintain strength and fitness. I decided to keep it.

I don’t do a lot of them, and I don’t need to suit up to get them done, so on the days when I don’t make time to suit up and seriously sweat, I still move my body and clear my mind. The bonus is a strong core and arms ready to haul lines when I arrive on Kagán, my sailboat, each spring. This discipline provides a base of fitness for me to build on.

Yoga As Muse:

When I first wrote fiction, I had a difficult time writing technically and creatively on the same day – the rhythms of the work were so different. I needed time, lots of it, to wait for inspiration to arrive. Given that reporting on field jobs was a big part of my paying work, writing a novel was going to be really hard (and it isn’t easy, in any case), if I couldn’t create inspiration, rather than wait for it.

When I first wrote fiction, I had a difficult time writing technically and creatively on the same day – the rhythms of the work were so different. I needed time, lots of it, to wait for inspiration to arrive. Given that reporting on field jobs was a big part of my paying work, writing a novel was going to be really hard (and it isn’t easy, in any case), if I couldn’t create inspiration, rather than wait for it.

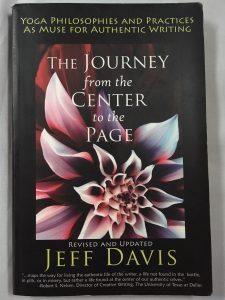

Then in 2007, I took the Yoga As Muse–Writing from the Center to the Page workshop with Jeffrey Davis at the UNM Taos Summer Writer’s Conference. The process Jeffrey taught, and I have practiced ever since, uses yoga to focus for writing. It goes something like this – you go to the mat and set intentions, the first intention is what you’re writing for (the big picture), and the second what you’re  writing for that day. Depending on the intentions, you select a specific sequence of yoga poses to help you move toward them. That’s a rudimentary description, and if you’re interested in trying it, I highly recommend Jeffrey’s book The Journey from the Center to the Page, Yoga Philosophies and Practices as Muse for Authentic Writing (Revised and Updated), published by Monkfish in 2008. Since learning the process and incorporating it into my writing life, I can switch gears from technical prose to creative work in a matter of minutes on the mat. I’m pretty kinesthetic, and for me, this discipline helps to quiet the mental chatter that often gets in my way. Sometimes I feel ready to write after just closing my eyes and setting my intentions, which can vary from drafting a new scene, to finding my characters’ true voices in dialogue, to simply staying at my desk and writing for an hour. Other days, I need to move for several minutes to find my direction, but I can’t think of a time that Yoga As Muse hasn’t enhanced my writing sessions.

writing for that day. Depending on the intentions, you select a specific sequence of yoga poses to help you move toward them. That’s a rudimentary description, and if you’re interested in trying it, I highly recommend Jeffrey’s book The Journey from the Center to the Page, Yoga Philosophies and Practices as Muse for Authentic Writing (Revised and Updated), published by Monkfish in 2008. Since learning the process and incorporating it into my writing life, I can switch gears from technical prose to creative work in a matter of minutes on the mat. I’m pretty kinesthetic, and for me, this discipline helps to quiet the mental chatter that often gets in my way. Sometimes I feel ready to write after just closing my eyes and setting my intentions, which can vary from drafting a new scene, to finding my characters’ true voices in dialogue, to simply staying at my desk and writing for an hour. Other days, I need to move for several minutes to find my direction, but I can’t think of a time that Yoga As Muse hasn’t enhanced my writing sessions.

My disciplines help me be who I strive to be – in these cases, someone who can lift her own weight and a writer – indeed, I have become what I practice. Maybe the little things aren’t so little at all.

What are your disciplines, little or big?

Note: You may know of the new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), that went into effect May 25, 2018. To help comply with GDPR consent, I’m confirming that you would like to continue receiving my blog. If you would like to remain on the list, you don’t need to do anything. However, if you would like to be removed from the list, please use the Unsubscribe link found at the bottom of any email sent by Geologist Writer. I do hope you’ll stay on as one of my valued readers. Thank you!

by D. J. Green | Apr 4, 2018 | Ground Work

In my novel, No More Empty Spaces, Will Ross, who is an engineering geologist beginning work in east central Turkey on a troubled dam, discovers a travertine deposit on his first day in the field.

Kayakale – kaya meaning rock, kale meaning castle – loomed above as Will shrugged his faded green canvas pack into a comfortable position on his shoulder. Seen from a distance the day before, he thought the stone pillar looked like travertine. The closer he got, the more it looked that way, but travertine wasn’t shown on any of the maps of the dam site.

Will squatted to inspect a boulder on the trail. Gray and rough and not distinctive to the untrained eye, the thin convoluted layers of the rock spoke of the heated waters that had dropped their calcareous mineral loads. The only hydrothermal deposits noted in the literature on the region were associated with the mines several kilometers downstream, near Kayakale village, but there was no doubt, this was travertine.

While cross-country skiing in Yellowstone in January, I also got to see travertines, fine crystalline calcium carbonate rocks formed by chemical precipitation. Common in areas with hot springs, travertines can form large terraces, like those in Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park and the hot springs of Pamukkale in southwest Turkey.

While cross-country skiing in Yellowstone in January, I also got to see travertines, fine crystalline calcium carbonate rocks formed by chemical precipitation. Common in areas with hot springs, travertines can form large terraces, like those in Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park and the hot springs of Pamukkale in southwest Turkey.

Generally white or tan, travertines can also bloom with color from mineral impurities. Though rough in texture in their natural forms, some travertines are prized for their beauty when cut and polished.

Refik, Will’s assistant, huffed up the trail just as Will reached for the Estwing rock pick that hung on his belt. Its handle was smooth and contoured to his hand, shaped over years of study and work. He swung the hammer. Metal rang on stone. Rock dust drifted up, depositing a thin film of grit on his lips. He blew the dust off the specimen in his hand.

“Travertine,” Will said, holding the rock out to Refik. “See how the fresh surface is pearlescent. Each of these layers,” he pointed to them, “was precipitated when hot, mineralized water daylighted and cooled. Cooler water can’t hold the minerals in solution that hot water can, so when the water flows out at the surface, minerals get deposited layer by layer.” He traced the layers with his finger. “Like this,” he said. “Do you understand?”

“Little,” Refik said. “Daha yavaş, lütfen. Hmmm. More slowly, please.”

“Okay. I mean, tamam.”

Refik smiled. “Çok iyi. Very good.”

Will opened the leather pouch on the other side of his belt from the pick and pulled out a brown glass vial with dilute hydrochloric acid. He squeezed a few drops onto the rock. The acid bubbled in the nooks and crannies.

“See? Definitely carbonate. Not that we didn’t know that. But travertine, so close to the dam site, that wasn’t reported. And it’s a big deal. Hot water can dissolve a lot more carbonaceous rock than water at ambient temps. The implications of travertine so near the dam site are immense with respect to the foundation and abutments. More dissolution means more and bigger cavities. Exactly what shut construction down.”

That’s how Will begins his work at Kayakale Dam. For those of us lucky enough to study geology as a profession, though we may do the same work day to day – mapping or trenching or drilling – each site presents its own landscape to read, its own geologic framework to understand, and its own puzzles to solve.

I hope you enjoy this short excerpt from No More Empty Spaces. The novel will be published on April 9, 2024. Stay tuned for information on pre-ordering it late in 2023. Read more from No More Empty Spaces.

.

The Chuckanut Formation sediments were deposited by a meandering river 50 million years ago. There were several depositional environments along the river, including braided streams, point bars, and oxbow lakes, resulting in numerous rock types within the formation – conglomerates to sandstones to siltstones.

The Chuckanut Formation sediments were deposited by a meandering river 50 million years ago. There were several depositional environments along the river, including braided streams, point bars, and oxbow lakes, resulting in numerous rock types within the formation – conglomerates to sandstones to siltstones.

Although Kagán is a sailboat, the wind doesn’t always blow, nor am I expert enough to maneuver under sail in tight spaces like into and out of marinas, so the auxiliary engine (a 37-horsepower marine diesel) is essential to our cruising life. At least every 10 hours of running time, we do an engine check – checking the engine oil and coolant levels, feeling the tension on the fan belt to the alternator, and taking a good long look for drips from the myriad hoses snaking through the engine. Though it doesn’t take much time, it’s a bit of a production – moving the companionway ladder, lifting off the forward engine cover, and crouching on hands and knees with a flashlight, reading glasses, and paper towels.

Although Kagán is a sailboat, the wind doesn’t always blow, nor am I expert enough to maneuver under sail in tight spaces like into and out of marinas, so the auxiliary engine (a 37-horsepower marine diesel) is essential to our cruising life. At least every 10 hours of running time, we do an engine check – checking the engine oil and coolant levels, feeling the tension on the fan belt to the alternator, and taking a good long look for drips from the myriad hoses snaking through the engine. Though it doesn’t take much time, it’s a bit of a production – moving the companionway ladder, lifting off the forward engine cover, and crouching on hands and knees with a flashlight, reading glasses, and paper towels.

While cross-country skiing in Yellowstone in January, I also got to see travertines, fine crystalline calcium carbonate rocks formed by chemical precipitation. Common in areas with hot springs, travertines can form large terraces, like those in Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park and the hot springs of Pamukkale in southwest Turkey.

While cross-country skiing in Yellowstone in January, I also got to see travertines, fine crystalline calcium carbonate rocks formed by chemical precipitation. Common in areas with hot springs, travertines can form large terraces, like those in Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park and the hot springs of Pamukkale in southwest Turkey.

Recent Comments