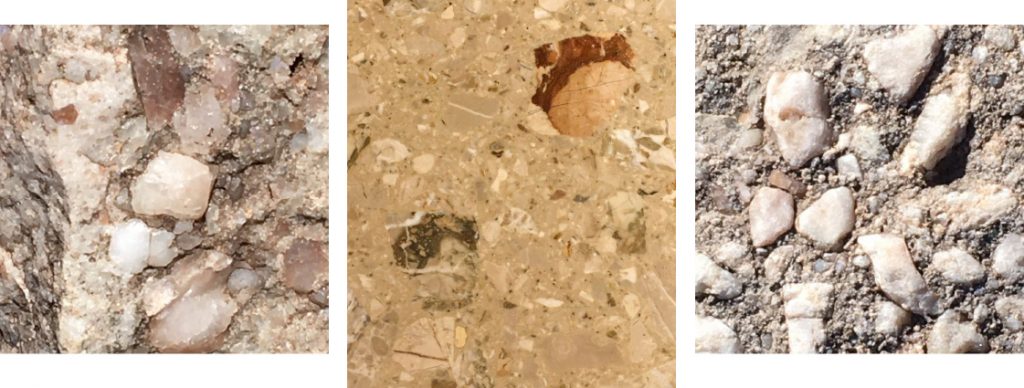

Breccia

Hunkered at home during the escalating pandemic is not, in fact, a terrible thing for a writer. There are fewer excuses to keep me from the work. So, last month I finished my novel (yes, again!) and my literary agent is now submitting it to publishers for consideration. I have also contemplated, and partially drafted, any number of pieces in recent months, but Wingbeats, my latest post, felt like one of the more important ones I’ve written since emerging from my library to your screens as a writer, and none of the other ideas carried the same urgency. Until now.

Windy today, I felt as buffeted about on my hike as I have been by the news since January 6th, when a storm of a sort I never imagined I would see in our country blew through the United States Capitol.

To duck out of the worst of the gusts, I dropped into a deep arroyo. Savoring the sudden calm, I stopped and settled onto a boulder. I could see the juniper boughs whipping in the wind above on the rim of the steep slope, but the wind had hushed around me. The metaphor of finding inner peace in the midst of chaos, not only in its absence, wasn’t lost on me. But it is winter, and too cold to linger for long. Rising, I stretched toward the sun, then bent at the waist, arms sweeping low my fingertips brushed the boulder’s surface. Straightening, I filled my eyes with the view and my lungs with the fresh mountain air, before heading the two or so miles down to my snug adobe home.

I have crossed this arroyo in previous wanderings, but never trekked up or down it. As expected (from the lessons I learned in Geology 101 decades ago), there are more and bigger boulders deposited in this high-gradient zone of the drainage than farther down, where the slope gentles and the drainage widens. This observation was more an unconscious taking in, less an academic analysis, as I wound around and scrambled over boulders of granite, limestone, and breccia.

Wait a minute, breccia? I’ve been hiking these hills for more than 20 years and I don’t recall seeing breccias before. They are coarse-grained sedimentary rocks in which angular clasts (rock fragments, for those not geologically inclined) are cemented in a finer-grained matrix. They can be quite beautiful, like these boulders, and are even polished as decorative stones. The shapes and colors of the clasts are intricate, interesting, and artful as only Mother Nature can be.

Since digging into words is as much my thing as rooting around in rocks, the etymology of breccia is Italian, meaning broken stones or rubble. With that, another metaphor occurs to me—the contrast of these ‘broken stones,’ this ‘rubble,’ to so many broken systems—the failure of our public health system, the systemic racism that pervades our society, the incongruity of how the White rioters who stormed the Capitol two weeks ago were treated compared to Black Lives Matter protesters flooding the streets in cities across the country this past summer, and the rubble left by those rioters bearing Confederate flags and symbols of white supremacy and neo-Nazism. Indeed, for millions worldwide, so many dreams have turned to rubble, so very many hearts have broken. It leaves me with few words, dazed by the grief of this moment in history.

Then I remember a long-ago conversation from a time I was overcome by grief of my own—about a broken heart being an open heart. Perhaps with all that is broken open, we can try to focus on the ‘open,’ rather than the ‘broken.’ Take the rubble, and build something beautiful with it.

Recent Comments